10 Reasons to Stop Drinking Diet Coke

"Diet soda can't be good for you."

Maybe you've heard this before. (Or said it yourself.)

After all, diet soda offers no vitamins or antioxidants, and it's usually artificially sweetened. So what, exactly, is "good" about it?

While that argument sounds logical, it doesn't answer the real question on everyone's mind:

Is diet soda actually bad for you?

And of related interest: Should you (or your clients) stop drinking diet soda?

To find out, we examined the body of research and talked to leading scientists and nutrition experts. Along the way, we asked lots of questions, including:

-

- Does diet soda lead to weight gain?

- Can it make you crave sugar?

- Does it affect your hormones?

- Can it mess with your microbiome?

- Does it cause cancer?

Plus: Why are some people so "addicted" to it?

The answers, found below, can help you decide if diet soda is right for you. (Spoiler alert: You'll even learn what's "good" about it.)

Does diet soda lead to weight gain?

Over the last two decades, several large observational studies have suggested a link between diet soda consumption and being overweight or obese.1, 2 (Other studies have shown benefits for weight control.)

"Is this because people are drinking these beverages to try to lose weight, or because the diet sodas are causing the weight gain?" asks Gail Rees, Ph.D., deputy head of the school of biomedical sciences at Plymouth University in England.3 "That's what we don't know."

Granted, this type of research doesn't show cause and effect. So it's not meant to be conclusive. But if there were a smoking gun, "high-intensity sweeteners" would be at the top of the suspect list.

If you're not familiar with the term "high-intensity sweeteners," it's the trendy way food scientists categorize zero- and very-low-calorie sugar substitutes. These substitutes include artificial sweeteners—like aspartame—and all-natural sweeteners, such as stevia.

There are eight high-intensity sweeteners approved for use in food by the United States' Federal Drug Administration (FDA)4:

- Saccharin

- Aspartame

- Acesulfame Potassium

- Sucralose

- Neotame

- Advantame

- Steviol Glycosides (stevia)

- Monk Fruit Extract (luo han guo)

While high-intensity sweeteners are used in thousands of food products, they've become notorious as a key ingredient in diet soda.

But observational studies on diet soda have an inherent challenge, beyond simply having to control for lifestyle factors (such as calorie intake, activity level, and smoking habits). Namely: They rely on food-frequency questionnaires, which means participants report their own intake.

So, for example, a research survey might initially ask a large group of study volunteers: How many diet sodas do you drink each week? From there, the scientists would run a statistical analysis to find correlations between diet soda intake and body weight (and other disease risk factors).

In nutrition research, this self-reporting is notoriously sketchy. Will the participants accurately remember what they ate or drank? Will they be honest? Will their answers provide a clear picture of their typical behavior?

All these variables can cloud the findings. But with high-intensity sweeteners, the takeaways are even murkier.

The reason: It's rare that someone knows what high-intensity sweetener they've been consuming.

What's more, sweeteners are combined to create a flavor more similar to sugar. Diet Mountain Dew, for instance, contains three sweeteners: aspartame, acesulfame potassium, and sucralose.5

As a result, high-intensity sweeteners are typically treated as one class of chemical in observational research. Yet each of these sweeteners may have very different effects on the body.

(To review the research yourself, check out this 2019 meta-analysis in the British Medical Journal or this 2017 review in Nutrition Journal. )

What if we studied high-intensity sweeteners individually?

Two years ago, at a conference on sweeteners, Richard Mattes, Ph.D., a professor of nutrition science at Purdue University and the director of The Ingestive Behavior Research Center,6 became frustrated by what he heard.

The researchers who took the podium were presenting wildly inconsistent results. Some linked high-intensity sweeteners to better health and weight loss, while others hedged toward disease and obesity.

"The findings contrasted so much," says Dr. Mattes. "And it struck me: Why do we think that these sweeteners would all behave the same way?"

After the Purdue conference, Dr. Mattes launched a trial that compared table sugar (sucrose) to saccharin, aspartame, stevia, and sucralose, individually.

For three months, he had 123 people consume 1.25 to 1.75 liters per day of a beverage sweetened with just one of the five sugar substitutes. (That's 42 to 60 ounces—or 3.5 to 5 cans of diet soda daily.) When the results came in, he found significant differences in how each sweetener affected body weight.7

Study participants consuming aspartame, stevia, and sucralose gained such little weight that the results were statistically equal to zero.

But those consuming saccharin, the artificial sweetener found in Sweet 'N Low, gained 2.6 pounds—about 60 percent as much as those consuming sucrose.

"That was a really surprising finding," says Dr. Mattes. "We expected people to gain weight with sucrose, but not with the low-cal sweeteners." (Note: These results haven't been replicated yet.)

Why the type of high-intensity sweetener might matter

Like many researchers, Dr. Mattes believes the difference lies in how sweeteners travel through our bodies.

Aspartame, for instance, the sole sweetener in Diet Coke8 and Dr. Pepper,9 is digested quickly in the upper third of the intestine and absorbed into the bloodstream as individual amino acids (aspartic acid and phenylalanine).6

The aspartame itself? "It's never going to get into the bloodstream, and it's not going to reach the colon," says Dr. Mattes. That limits its ability to wreak havoc, he says.

Neotame, which isn't widely used, is also thought to be rapidly digested,10 while other sweeteners continue through the digestive tract to be broken down in varying degrees by enzymes.6

Stevia and sucralose—the high-intensity sweetener we consume the most—appear in large quantities in the colon, while saccharin (along with acesulfame potassium, which wasn't included in Dr. Mattes' study) shows up more readily in the bloodstream.6

"The idea that we can view them all as a single class of substances is likely wrong," says Dr. Mattes. "To study their health effects, we're going to have to look at them individually." (And ultimately, in different combinations with one another, too.)

And that, says Dr. Mattes, is where the research is headed. In the coming years, we'll see more studies that put the focus on specific sweeteners, rather than the class as a whole.

All of which isn't to dismiss findings from observational research. To prove, however, that high-intensity sweeteners, and thus diet soda, can cause weight gain, researchers need to find the mechanism through which it happens. And while there are theories, none have yet to emerge as fact. Here's what the research looks like right now.

Theory 1: Diet soda makes you addicted to sugar

The idea: Sweet foods and beverages alter your taste preference, so you crave more sweet foods. That, in turn, could make it more difficult to turn down dessert or break-room doughnuts.

"It's well-established that consuming sugar-sweetened foods can increase your desire for sweets," says Brian St. Pierre, M.S., R.D., director of nutrition at Precision Nutrition. "You tend to crave whatever you eat habitually, and this seems to be true for both sugary and non-sugary foods."

But does consuming high-intensity sweeteners, specifically, make you want sweets? The research isn't clear.

Most studies that suggest high-intensity sweeteners increase the desire for sweet foods have been done on rats. In fact, in a 2019 meta-analysis published in the British Medical Journal ,1 researchers found just two randomized controlled trials that tackled the question of sweet preference head-on in humans. And they did it by adding aspartame to the diets of overweight and obese subjects.

The conclusion of those studies: Among those who consumed the high-intensity sweetener, the desire to eat sweet foods was slightly lower.

"There's some evidence that consuming a diet version of a sweet food can actually help satisfy your desire for sweets," says St. Pierre. "Especially if you're used to consuming a sugary soda and replace it with a diet drink."

There's also this possibility: The effect could be highly individual. Perhaps this is a problem for some but not for others.

Theory 2: Diet soda affects your hormones

The proposed mechanism here: High-intensity sweeteners "trick" your body into thinking you're eating sugar. This triggers your pancreas to release the hormone insulin, which signals your body to slow the breakdown of fat. As a result, it could be harder to lose weight.

A small insulin bump has been observed in studies on sucralose11 and saccharin, but one study of 15 young men failed to find the response for aspartame.12 Overall, human studies show these insulin spikes are so small they're hard to detect and very short-lived. Which makes it unlikely they impact weight loss at all, given what we know now.

Plus, even if there were a significant insulin release, your ability to lose weight is most dependent on your overall energy balance, not insulin, says St. Pierre. (For more background, read: Calories in versus calories out? Or hormones? The debate is finally over.)

Theory 3: Diet soda disrupts your microbiome

What if high-intensity sweeteners alter your microbiome? "That could have implications for energy balance, appetite, immune function—all kinds of things," says Dr. Mattes.

As with other issues, Dr. Mattes believes any impact could be dependent on the type of sweetener used. Those that make their way to your colon, for instance—such as stevia, sucralose, and to some extent, saccharin—might be more likely to present problems, he says.

While this is an intriguing area of research, it's still in its infancy. "There are some interesting animal studies, but not a whole lot on humans," says Mark Pereira, Ph.D., a professor of community health and epidemiology at the University of Pittsburgh.13 And of the human studies that do exist, he says, "They just aren't very good."

Now, all of this might seem like a whole lot of nothing. But it's useful to know where these theories stand for one reason: It gives you a better sense of the existing scientific evidence. (Especially useful when reading Facebook comments on the topic.)

Of course, these aren't the only ways a no-calorie diet soda could lead to weight gain. Some studies have suggested that consuming high-intensity sweeteners may increase hunger, by perhaps interfering with appetite hormones and how your brain regulates food intake (or by some other mechanism).2 But even more studies have shown no effect at all.

"The idea that high-intensity sweeteners increase hunger seems to only be true if they're consumed alone, in the absence of other nutrients," says St. Pierre. "This doesn't, however, seem to be the case when they're consumed with meals, although the data is very limited and far from conclusive."

But in considering all this research, it's important to remember: "If you currently drink a lot of regular soda, or have in the past, diet soda is a better option based on what we know today, even if it's not perfect," says St. Pierre. "There's far more data on weight and health problems associated with sugar-sweetened beverages than there is with high-intensity sweeteners."

What about cancer and other serious health problems?

In the 1970s, saccharin was linked to bladder tumors in rats.14 For a while, the sweetener was even banned from foods and beverages in the U.S.

But the cancer link never emerged in humans, and as a paper from Current Oncology notes, you'd have to drink 800 cans of diet soda per day to reach the dose used to induce cancer in rats.15

Still, the cancer scare means that every high-intensity sweetener since saccharin has faced increased scrutiny.

"There are still people out there who claim that [high-intensity sweeteners] are associated with cancers," says Dr. Mattes. "But every governmental body that has reviewed them—they've done it extensively in the United States, Australia, Europe, Japan, and Canada—concludes that when used in reasonable amounts, they're not harmful."

If that sounds less than comforting, that's understandable. Especially given how much there is to learn about the way individual high-intensity sweeteners are processed by the body.

But currently: There's no good evidence to suggest any of the FDA approved sweeteners pose serious health risks.

In fact, the chart below shows the daily intake of these sweeteners that the FDA has deemed acceptable for a 150-pound (68 kg) person.4

| Sweetener | Number of times sweeter than table sugar | Acceptable daily limit for a 150-pound (68 kg) person |

|---|---|---|

| Acesulfame Potassium (Sweet One®, Sunnett®) | 200x | 1,020 mg |

| Advantame | 20,000x | 2,230 mg |

| Aspartame Nutrasweet®, Equal®, Sugar Twin® | 200x | 3,400 mg |

| Neotame (Newtame®) | 10,000x | 20.4 mg |

| Saccharin (Sweet and Low®, Sweet'NLow®) | 400x | 1,020 mg |

| Sucralose (Splenda®) | 600x | 340 mg |

* Adapted from United States FDA chart on Acceptable Daily Limit of High-Intensity Sweeteners

For perspective, here are the amounts of high-intensity sweeteners you'll reportedly find in several popular 12-ounce cans of diet soda16:

| Diet Coke | 187.5 mg aspartame |

| Diet Coke with Splenda | 45 mg acesulfame potassium + 60 mg sucralose |

| Coke Zero | 87 mg aspartame + 46.5 mg acesulfame potassium |

| Diet Pepsi | 177 mg aspartame* |

| Pepsi One | 45 mg acesulfame potassium + 60 mg sucralose |

| Diet Dr. Pepper | 184.5 mg aspartame |

| Diet Mountain Dew | 85.5 mg aspartame + 27 mg acesulfame potassium + 27 mg sucralose |

| Sprite Zero | 75 mg aspartame + 51 mg acesulfame potassium |

* Since this analysis, Diet Pepsi has adjusted their formula in the U.S. It's now sweetened with aspartame and acesulfame potassium (precise amounts not available).

** Adapted from Diabetes Self-Management, "Diet Soft Drinks" by Mary Franz, MS, RD, LD

Of course, few people will guzzle 19 cans of Diet Coke a day. (We'll stop short of saying "no one," because… people.) That's the amount that'd put you over the acceptable daily limit from diet soda alone.

But keep in mind: High-intensity sweeteners are used in far more than diet soda. You'll find them low-calorie yogurts, energy drinks, baked goods, diet desserts, and protein powders and bars.

And just because you're under that limit for diet soda doesn't mean you're drinking what most health experts would consider "reasonable amounts."

Here at Precision Nutrition, our coaches say it's not unusual for new clients to report they're drinking six or more 20-ounce diet sodas a day. That's a lot, by any measure. These folks often claim they're hooked on it. Which leads us to this question…

Why can't you stop drinking diet soda?

If you're a diet soda diehard, maybe you've wondered why you can't get enough. Plenty of people even say it's downright "addictive." (To learn more, read: Eating too much? Blame your brain.)

You can be sure: That's no accident.

"Food and beverage manufacturers scientifically engineer products, including diet soda, to appeal to the pleasure centers in your brain, belly, and mouth," says Brian St. Pierre, M.S., R.D., Precision Nutrition's Director of Nutrition. "That drives you to consume more of it than you might otherwise."

The sweetness is no doubt part of diet soda's allure. But the other big factors? Carbonation, caffeine, and flavor enhancers.

"All combined, this is known as stimuli stacking," says St. Pierre. "It's how companies engineer foods and drinks to make them nearly irresistible."

The weird reason you love carbonation

Ironically, the appeal of carbonation is that it hurts: The CO2 burns your tongue. Like the Tabasco on your eggs, the pain is mild and enjoyable. It also occurs through an entirely different pathway.

"Enzymes in your mouth convert CO2 into carbonic acid," says Paul Breslin, Ph.D., a member of the Monell Chemical Senses Center and a professor of nutritional sciences at Rutgers University.10 "That can actually acidify the tissue, so it will hurt a little bit."

The pain increases as the bubbles sit on your tongue, and that creates a built-in customization mechanism. Someone who likes more of this pain can simply savor each sip longer.

In addition to the mouth thrill of a minor burn, carbonation amplifies the signal coming from the liquid, so it quenches your thirst better than flat water.10

The likely reason: It provides more sensory data for your brain to latch onto. "When you start playing with the sensory properties of the beverage, you can sort of make it hyper-stimulatory," says Dr. Breslin. This can make a diet soda seem more refreshing than water, even before you factor in sweetness.

Caffeine: Diet soda's little helper

Caffeine is next in line to explain diet soda's popularity. Although it's known as a productivity booster, it also adds a slight bitterness to cola.

"People who make sodas have a tendency to say caffeine is there to affect the flavor," says Dr. Breslin. "But there's another camp that says the caffeine is at a level you can feel systemically, like a caffeine buzz that you would get from tea or coffee."

To be fair, diet soda's dosing is relatively small compared to coffee. A 12-ounce can of Diet Coke contains 46 milligrams (mg) of caffeine8, and Diet Pepsi has slightly less.17 That's about half of what you'd find in an eight-ounce cup of joe,18 and less than 20 percent of a tall Starbuck's Pike Place Roast.19

But again, it's common for coaches to report their clients are drinking a two-liter bottle of diet soda daily. And all that caffeine adds up.

Plus, the smaller caffeine dosage could lure people into thinking soda is okay to drink with dinner or before bedtime, which could interfere with sleep and even lead to weight gain.

A study from the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine found that reducing people's natural sleep times by a third (roughly 2.5 hours) caused them to consume 559 extra calories per day.20 And no, the sleep-deprived subjects didn't use their extra waking hours to work out: Despite eating more, their caloric output remained flat.

Flavor enhancers: The X-factor

Why is Coke more popular than Pepsi?

Not because it's sweeter or more carbonated or has more caffeine. It's all the ingredients together, including the patented flavor enhancers that make Coke… taste like Coke.

"These ingredient combos stimulate the reward and hedonic centers of your brain," says St. Pierre. "They also tap into the nature of human behavior."

Let's say you try diet soda and enjoy it. So, like any normal human, you start drinking it regularly. "After a lot of consistent consumption, your brain comes to rely upon and expect the pleasure hit it gets from the drink's ingredients," says St. Pierre. "And that drives you to drink even more."

So, should you drink diet soda… or not?

There's no clear-cut answer that applies to everyone.

As is often the case, the "right" choice isn't dictated by the science alone. Instead, it's dependent on what makes the most sense for you, the individual—with respect to both the evidence and your personal preferences, lifestyle, goals, and current intake.

Experts who recommend cutting out diet soda are essentially following the precautionary principle: Until something is proven without-a-doubt safe, it's better to assume it isn't. (Read: Phrases like "generally recognized as safe" and "acceptable daily intake" don't cut it.)

That might seem overly cautious to you, or it might make complete sense. Neither approach is wrong.

But that brings us to the diet soda drinker's dilemma, and the real reason you're still reading this article: What if you love diet soda, but you're still concerned with how it might affect your health?

Step 1: Worry about what really matters first.

Based on the scientific evidence, there's no compelling reason to stop drinking diet soda entirely.

"The risks of having excess body fat, on the other hand, are well-known and significant," says St. Pierre. "If you're replacing regular soda, or another highly caloric beverage, with diet soda, and it's helping you lose weight or maintain a healthy weight, the benefits outweigh any potential downside."

Besides helping with weight control, there are other ways diet soda can support your health and fitness goals.

Maybe you've decided to drink less alcohol, and diet soda feels like a compromise you can live with in social situations. Or you want to have some caffeine in the morning or before your workouts, and you just don't like unsweetened coffee or tea. (See, diet soda is good for something!)

Think of the effort you spend on your health as a jar, says St. Pierre. If you have a choice between big rocks, pebbles, and sand, you'll be able to fill up your jar fastest with big rocks. Afterward, you can fill in the cracks with smaller stuff, like pebbles and sand.

In the grand scheme of things, whether you choose to drink diet soda is a small rock. It might even be sand, says St. Pierre.

So, before you worry about changing your diet soda habits, focus on "big rocks" that make the most impact on your health, such as:

- eating mostly minimally-processed whole foods

- eating enough lean protein and vegetables

- eating slowly, until satisfied, and only when hungry

- getting adequate sleep

- managing stress

- moving regularly

- reducing excessive smoking/alcohol consumption

Unlike eliminating diet soda, there's a wealth of evidence showing the above habits have a lasting effect on your overall health. Tackle the big stuff first. (Coaches: This advice applies when helping your clients, too.)

Three additional notes on health:

1. People with phenylketonuria, a rare genetic disease that makes metabolizing phenylalanine difficult, should avoid products with aspartame altogether. (Aspartame is composed of phenylalanine.)

2. Diet sodas tend to be highly acidic, which can erode tooth enamel. In fact, a recent study published in the Journal of American Dental Association found most diet sodas to be "erosive" or "highly erosive."21 For context, though, many flavored waters, bottled teas, and juice, sports, and energy drinks also met these designations.

3. Carbonation, caffeine, and high acidity can all cause acid reflux individually, says St. Pierre. And since many diet sodas contain all three, they're among the worst triggers. Which is worth considering, in case you regularly suffer from reflux or heartburn.

Step 2: Lose the all-or-nothing mindset.

If you decide you want to drink less diet soda, you don't have to go cold turkey.

In fact, there's a wide range of choices available between drinking nothing but water and drinking a two-liter of Diet Pepsi a day.

For example:

- If you drink four diet sodas a day, could you substitute green tea for the morning one?

- If you normally have a diet soda every night with dinner, could you do that just three times a week instead?

- If you constantly crave the bubbly mouthfeel of diet soda, could you swap one or two a day for carbonated water (such as seltzer or sparkling)?

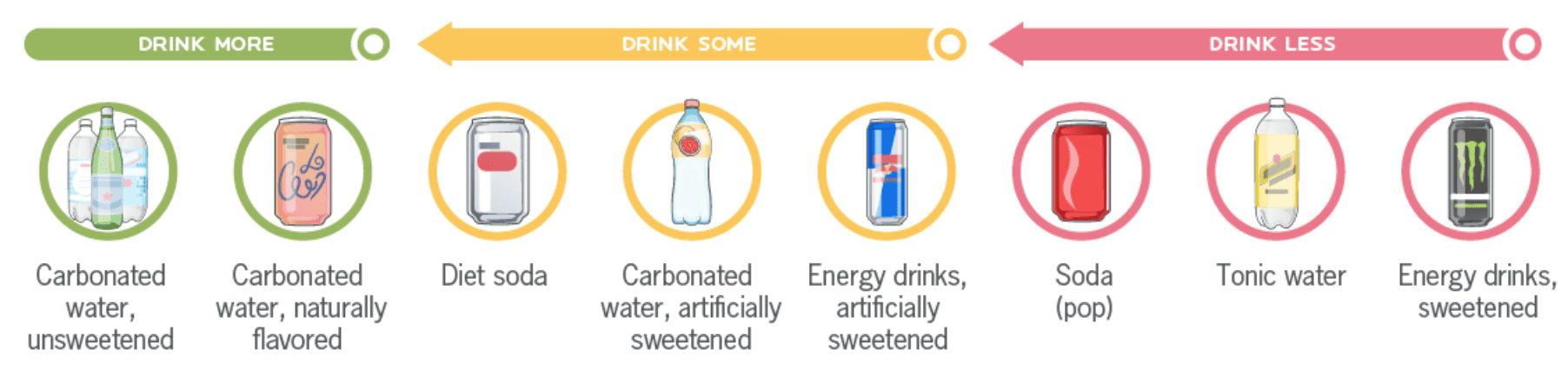

St. Pierre uses this chart to help clients see how they can make slightly better choices, one drink at a time. The goal isn't to completely eliminate drinks you love, but rather, shift your habits toward the "drink more" category. (See our "What to drink" guide for complete recommendations and strategies.)

At first, these tweaks might not seem like much. But small, consistent changes made over time add up to lasting change.

As a rule of thumb, St. Pierre does recommend a "reasonable amount" target of 8 to 16 ounces a day. Why? Because this amount:

- Ensures you're well within the "acceptable daily limit," as determined by the FDA or your country's governing agency

- Allows for the inclusion of other items that contain high-intensity sweeteners (such as protein powders and no-calorie sweeteners for coffee and tea)

- Keeps intake low enough to protect your teeth from erosion

- Leaves plenty of room for beverages known to be health-promoting, such as plain water, tea, and coffee

Step 3: Remember: There's no "best" way to eat… or drink.

As much as a universal, one-size-fits-all, "best diet ever" might make our lives simpler… it doesn't exist.

Instead, it's about finding a way of eating (and drinking) that works best for you as an individual.

Good nutrition is the goal, and it's possible to accomplish that in a way you actually like. Even if it includes drinking diet soda daily.

If you're a coach, or you want to be…

Learning how to coach clients, patients, friends, or family members through healthy eating and lifestyle changes—in a way that's evidenced-based and personalized for their unique body, goals, and preferences—is both an art and a science.

If you'd like to learn more about both, consider the Precision Nutrition Level 1 Certification. The next group kicks off shortly.

What's it all about?

The Precision Nutrition Level 1 Certification is the world's most respected nutrition education program. It gives you the knowledge, systems, and tools you need to really understand how food influences a person's health and fitness. Plus the ability to turn that knowledge into a thriving coaching practice.

Developed over 15 years, and proven with over 100,000 clients and patients, the Level 1 curriculum stands alone as the authority on the science of nutrition and the art of coaching.

Whether you're already mid-career, or just starting out, the Level 1 Certification is your springboard to a deeper understanding of nutrition, the authority to coach it, and the ability to turn what you know into results.

[Of course, if you're already a student or graduate of the Level 1 Certification, check out our Level 2 Certification Master Class. It's an exclusive, year-long mentorship designed for elite professionals looking to master the art of coaching and be part of the top 1% of health and fitness coaches in the world.]

References

Click here to view the information sources referenced in this article.

- Toews, I., Lohner, S., Kullenburg de Gaudry, D., Sommer, H., Meerphohl, J, (2019). Association between intake of non-sugar sweeteners and health outcomes: Systematic review and meta-analyses of randomised and non-randomised controlled trials and observational studies. British Medical Journal.

- Lohner, S., Toes, I., Meerpohl, J.J. (2017). Health outcomes of non-nutritive sweeteners: analysis of the research landscape. Nutrition Journal, 16(55).

- Gail Reese, Ph.D., deputy head of the school of biomedical sciences at Plymouth University in England.

- Additional information about high-intensity sweeteners permitted for use in food in the United States. (U.S. Food and Drug Administration.)

- Nutrition facts for Mountain Dew.

- Richard Mattes, Ph.D., professor of nutrition science at Purdue University and the director of The Ingestive Behavior Research Center.

- Higgins, K.A., Mattes, R.D. (2019). A randomized controlled trial contrasting the effects of 4 low-calorie sweeteners and sucrose on body weight in adults with overweight or obesity. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 109(5): 1288-1301.

- Nutrition facts for Diet Coke.

- Nutrition facts for Dr. Pepper.

- Paul Breslin, Ph.D. Member of the Monell Chemical Senses Center and professor of nutritional sciences at Rutgers University.

- Dhillon, J., Lee, J.Y., Mattes, R.D. (2017). The cephalic phase insulin response to nutritive and low-calorie sweeteners in solid and beverage form. Physiology and Behavior, 181: 100-109.

- Duskova, M., Macourek, M., Sramkova, M., Hill, M., Starka, L. (2013). The role of taste in cephalic phase of insulin secretion. Prague Medical Report, 114(4): 222-30.

- Mark Pereira, Ph.D., a professor of community health and epidemiology at the University of Pittsburgh.

- Reuber, M.D. (1978). Carcinogenicity of saccharin. Environmental Health Perspectives, 25: 173-200.

- Touyz, L. Z. G., (2011). Saccharin deemed "not hazardous" in United States and abroad. Current Oncology, 18(5): 213-214.

- Franz, M. (2010). Diet soft drinks. Diabetes Self-Management.

- Caffeine content of Diet Pepsi.

- Food Data Central. United States Department of Agriculture.

- Nutrition information for Starbucks Pike Place Roast.

- Calvin, A.D., Carter, R.E., Adachi, T., ,Macedo, P.G., Albuquerque, F.N., van der Walt, C., Bukartyk, J., Davison, D.E., Levine, J., Somers, V.K. (2013). Effects of experimental sleep restriction on caloric intake and activity energy expenditure. Chest, 144(1): 79-86.

- Reddy, A., Norris, D.F., Momeni, S.S., Waldo, B., Ruby, J. (2016). The pH of beverages available to the American consumer. Journal of the American Dental Association, 147(4): 255-263.

If you're a coach, or you want to be…

Learning how to coach clients, patients, friends, or family members through healthy eating and lifestyle changes—in a way that's personalized for their unique body, preferences, and circumstances—is both an art and a science.

If you'd like to learn more about both, consider the Precision Nutrition Level 1 Certification.

10 Reasons to Stop Drinking Diet Coke

Source: https://www.precisionnutrition.com/diet-soda